Low Back Pain in Pregnancy: What It Really Means — and What Actually Helps

TL;DR

Low back pain in pregnancy is extremely common, but it is rarely random—and you do not have to simply endure it. Most pregnancy back pain is linked to ligament laxity, shifting load through the pelvis, and compensatory muscle overuse. Stretching alone is seldom the solution. Functional movement, pelvic stability, and individualized support matter far more. The right tools—such as an SI joint belt or maternity belly band—may help, but they work best alongside movement retraining. And because most yoga teachers are not trained in perinatal biomechanics, specialized guidance can make a meaningful difference.

You deserve precision, not vague labels.

Why Low Back Pain Is So Common in Pregnancy (and What’s Really Happening)

Low back pain is one of the most frequently reported physical complaints during pregnancy. Depending on the study, between roughly half and two‑thirds of pregnant people will experience it at some point. It is common—but common does not mean inevitable, and it certainly does not mean you must simply tolerate it.

As your body adapts to a growing baby, several things happen at once. Your center of gravity shifts forward. Your pelvis is supporting more weight (womb, baby, and surrounding tissues). Hormones such as relaxin increase ligament laxity. The sacroiliac joints and surrounding tissues become more mobile. As passive stability decreases, your body relies more heavily on muscular support to keep everything organized.

This is often where the story of “tightness” begins.

Your hamstrings may feel tight. Your hips may feel grippy. Your low back may feel overworked. Your psoas may feel like it never turns off.

Very often, this is not because your body needs more stretching. It is because your body is working harder to stabilize a system that is changing quickly. In many cases, those achy, tight muscles are responding to overuse and compensation—not a true need for more stretching.

Tight Does Not Always Mean Short

Many pregnant people are told their hamstrings are tight and need stretching. The same is often said about the psoas.

But in pregnancy, tight often means protective.

The hamstrings attach to the sitting bones and assist in stabilizing the sacroiliac joints. When the pelvis becomes more mobile, they increase tone to help control movement. The psoas stabilizes the lumbar spine and may increase tone to maintain structural integrity as ligament support softens.

Aggressively stretching these muscles without addressing the underlying instability may temporarily relieve symptoms while worsening the root issue.

Relief is not the same as resolution. In many cases, what helps most is restoring functional hamstring length alongside improved pelvic stability and movement mechanics, which can contribute to meaningful reduction in back pain. Katy Bowman’s work in Nutritious Movement highlights how the hamstrings influence pelvic mechanics and why restoring usable length—rather than aggressively forcing stretch—often improves overall load transfer.

One simple place to begin is with a supported hip hinge drill: stand facing a wall with your feet about hip‑width apart and a foot or so away from the wall. Keeping your spine long, gently send your hips back toward the wall as if you are trying to tap it with your sitting bones. You should feel your hamstrings lengthen while your spine stays relatively neutral. This pattern helps retrain the body to share load through the hips and glutes instead of the low back.

The Psoas Conversation

A lot of well‑meaning yoga teachers will tell pregnant and postpartum individuals to “release the psoas” to fix low back pain. While psoas down‑regulation can be part of a comprehensive plan, treating it as a stand‑alone solution is not considered a reliable clinical strategy—especially in pregnancy and postpartum, where lumbopelvic stability is already changing (Garner; Duvall).

The psoas is not just a hip flexor. It is also a stabilizer for the lumbar spine and pelvis. If the pelvis is unstable, the psoas may increase tone because it is literally helping hold your bones together.

In many cases, an overactive or “tight” psoas is compensating for under‑recruitment elsewhere—most commonly the glutes, the deep core (including the transverse abdominis), and the broader load‑sharing system of the pelvis. Research and clinical models of lumbopelvic stability emphasize that coordinated activation of the deep abdominal wall, pelvic floor, and hip musculature is central to spinal support (Richardson, Hodges, & Hides, 2004; Duvall).

This means that simply trying to stretch or manually release the psoas in isolation often misses the bigger picture. Meaningful and lasting relief typically comes from restoring balanced force distribution through the system.

This is where glute strength, transverse abdominis coordination, and everyday movement mechanics come into play. When these stabilizers begin doing their share of the work, the psoas often reduces its protective tone on its own.

Posture and alignment matter here, too. Improving how you stand, hinge, squat, carry, and transition through daily life naturally recruits the deep core and hip stabilizers throughout the day. Over time, this can decrease the need for the psoas to overwork.

In other words, this is not just about doing more ab exercises or more glute exercises. It is about retraining the brain–body connection so the right muscles fire at the right time. When load is shared more efficiently across the system, those overworked, “tight” psoas muscles often finally get permission to soften.

This is also where working individually 1:1 with a functional movement teacher—such as myself—can be profoundly supportive. Personalized guidance often accomplishes far more than hours spent in a general class unknowingly reinforcing the very patterns contributing to your discomfort.

So when someone tells you to “just release it,” pause and ask a better question: what is the psoas doing extra work for?

Functional Movement Is the Turning Point

Low back pain in pregnancy is very often a load management issue, a motor control issue, or a body mechanics issue.

Learning to hip hinge—bending from the hips instead of rounding through the spine—redistributes load into the glutes and away from the lumbar spine. Refining how you squat or lunge to lift objects changes daily strain patterns. Coordinating breath with movement improves deep core function and pelvic stability.

These are not fitness trends.

They are rehabilitation principles embedded into daily life. As the body changes throughout pregnancy and postpartum, paying attention to how you move in a functional way becomes more important than ever. It is very easy to compensate through movement, but as the body grows and expands in pregnancy—and then slowly reorganizes after birth—good function helps ease these transitions and supports long‑term postpartum restoration.

It is also important to remember that after birth, the body does not magically return to its pre‑pregnancy state. Recovery is often a gradual, years‑long process influenced by many factors. Even when the body looks “normal” again externally, there may still be internal changes or lingering movement habits from the postpartum period that benefit from thoughtful, functional retraining.

Why Malasana Feels So Good—and When It Doesn’t

Many pregnant people experience relief in a supported yogic squat (Malasana), and there is a clear biomechanical reason why.

Malasana

In a deep squat, the hips flex and the sacrum gently counternutates. The coccyx shifts posteriorly. The orientation of the pelvic outlet changes. Research in obstetric biomechanics has demonstrated that upright and squatting positions can increase pelvic outlet dimensions compared to supine positions (Gupta et al., 2012; de Jonge et al., 2004).

Additionally, deep hip flexion lengthens the pelvic floor in a supported way. The levator ani and associated muscles adjust in length and tension, while the deep hip rotators shift orientation. Imaging and biomechanical studies of pelvic floor behavior in different positions support the concept that pelvic floor length and load‑sharing change with hip flexion and squat‑like postures (Bø et al., 2015; Hodges et al., 2007). For many bodies, this creates shared load, reduced lumbar compression, and a sense of decompression.

It feels good because the body is no longer fighting gravity alone.

However, context matters.

If baby is breech, transverse, or not yet optimally positioned late in pregnancy, repeated deep symmetrical squatting may encourage descent before rotation has occurred. While babies do not permanently get stuck, early sustained engagement can reduce available space for positional shifts.

Malasana is powerful. It is not universal.

From a movement perspective, whole‑body squat mechanics also depend heavily on adequate hip mobility and coordinated glute and pelvic floor function, themes emphasized in the work of Katy Bowman and other biomechanics educators. When the squat is supported and well‑aligned, it can distribute load more efficiently through the hips rather than the lumbar spine.

When Practitioners Say “Pelvic Girdle Pain”

You may also hear your symptoms described as pelvic girdle pain. This term can be useful—but it is also very broad.

The pelvic girdle refers to the entire ring of the pelvis: the sacrum in the back, the hip bones on the sides, the pubic symphysis in the front, and the surrounding muscles, ligaments, and connective tissues. When someone says “pelvic girdle pain,” they are describing a region—not a specific root cause (Vleeming et al., 2008).

Under this umbrella can live low back pain, sacroiliac joint irritation, hip joint pain, pubic symphysis dysfunction (SPD), deep pelvic floor tension, nerve irritation, or some combination of these. These issues are intertwined because the pelvis functions as a ring, but they are not identical and often benefit from slightly different strategies (Wu et al., 2004).

During pregnancy, hormonal softening of connective tissue means the pelvis relies more heavily on muscular coordination for stability. If that coordination does not adapt efficiently, the pelvic girdle can feel unstable and painful.

This is not because your body is failing.

It is because it is adapting.

If you are given the label “pelvic girdle pain” without further education, guidance, or referral, it may reflect an older, less precise care model. Modern best practice recognizes that pregnancy‑related lumbopelvic pain is multifactorial and often benefits from targeted movement support and, when appropriate, pelvic health physical therapy (Vleeming et al., 2008).

This is also where individualized support can make a meaningful difference. Working 1:1 with a functional movement specialist—such as myself—allows us to assess your specific presentation and build a plan tailored to your body, your pregnancy, and your postpartum recovery. In many cases, clients are able to use HSA or FSA funds when their medical provider writes an appropriate referral or letter of medical necessity. If you’re curious whether this could apply to you, I’m always happy to help you explore the process.

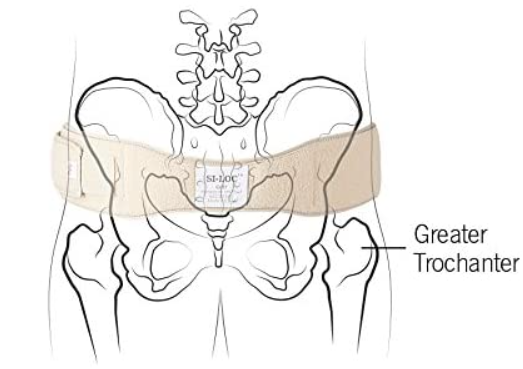

External Support: SI Belts and Belly Bands

Sometimes the most compassionate thing we can do is give your pelvis a little help.

Research supports pelvic (sacroiliac) belts as potentially helpful for pregnancy‑related pelvic girdle and low back pain. Studies suggest SI belts may improve function, reduce pain, and assist load transfer by providing external compression and stability to the pelvic ring (Mens et al., 2006; Bertuit et al., 2018; Fitzgerald et al., 2022). Biomechanical work also suggests belts can positively influence gait parameters and pelvic stability in pregnant populations with pelvic girdle pain.

Maternity support garments (often called belly bands) have also been studied. A systematic review found these garments may help reduce low back and pelvic pain, improve function and mobility, and support comfort during pregnancy, although mechanisms and long‑term effects are still being clarified.

These tools can be very helpful.

They are also not substitutes for strength, coordination, and movement education.

If you are looking for a supportive SI belt, I often recommend this option for my clients: https://amzn.to/4rKpoe1

Affiliate disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, I may earn from qualifying purchases at no additional cost to you. I only recommend products I genuinely use and trust in my practice.

As always, the right fit and placement matter—and individualized guidance can help you get the most benefit from any support device.

Waist Trainers Are Not Postpartum Recovery Tools

It is important to distinguish supportive postpartum binders from waist trainers popularized by celebrities and influencers.

Waist trainers are rigid compression garments designed to reshape the waist. They often restrict breath, increase intra‑abdominal pressure, and may place additional strain on a healing pelvic floor.

Supportive postpartum wrapping, by contrast, is intended to provide gentle containment and comfort during early recovery. Learn more about belly binding in my article Belts, Bands, and Binders — Oh My! (COMING SOON)

Healing is not the same as shaping.

Alignment Matters (Yes, Even in Yoga)

Many yoga teachers were trained in alignment systems that were not developed from modern biomechanics research. While often well‑intentioned, non‑biomechanical cueing can repeatedly place joints into end‑range positions that gradually stress and degrade surrounding tissues.

The body is remarkably adaptable—but it also keeps score. When we repeatedly load joints in positions that exceed their optimal capacity, the surrounding structures can become irritated over time.

Warrior II Conundrum

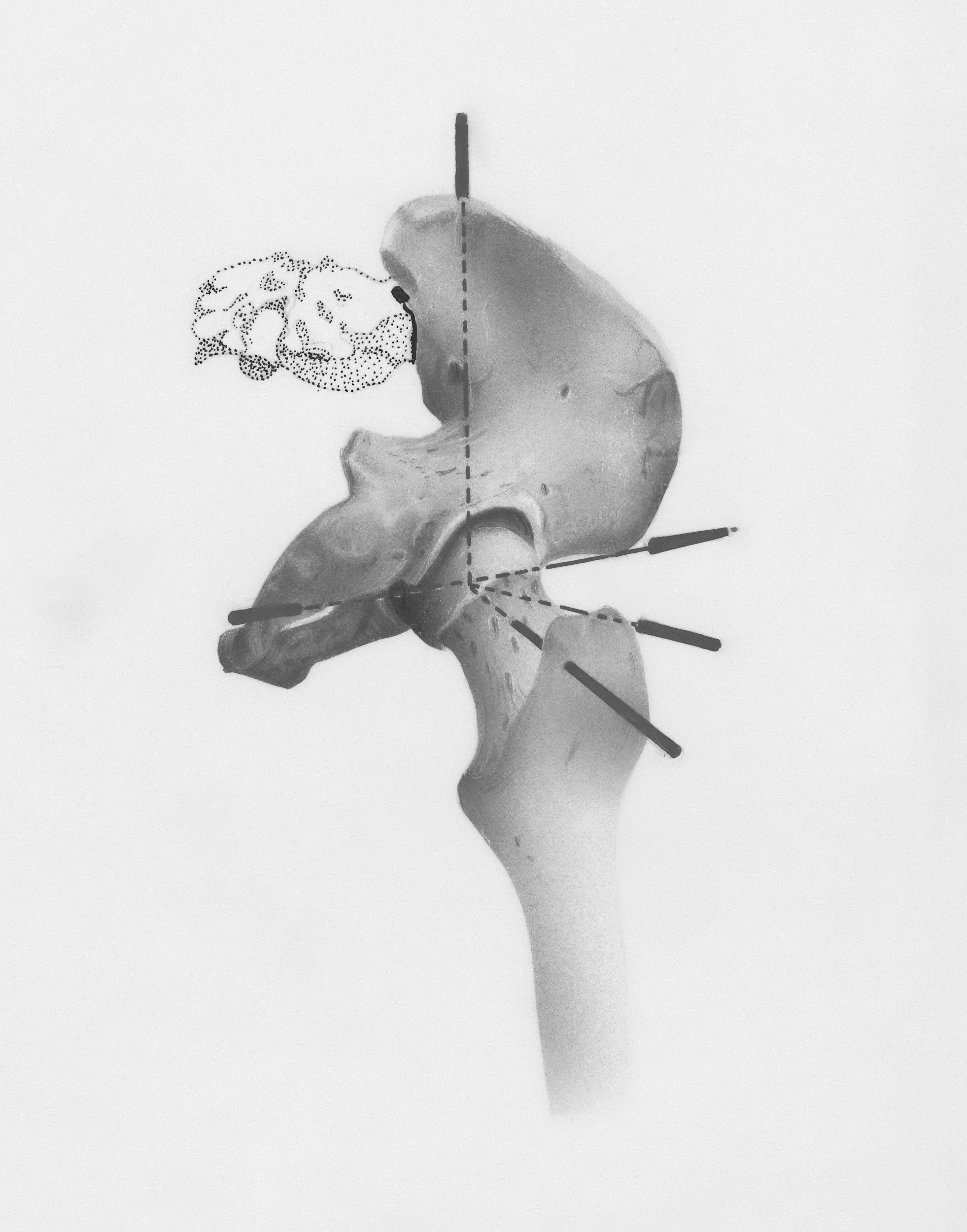

A common example appears in Warrior II. Traditional cueing sometimes encourages students to square the back foot fully and externally rotate the hip to match the front leg orientation. For some bodies, this creates excessive external rotation torque at the hip joint. Over months or years of practice, repeated end‑range loading may contribute to irritation of the acetabular labrum—the fibrocartilaginous structure that helps stabilize the hip joint (Garner; Lewis et al., 2018).

It’s important to clarify:

Yoga itself does not inherently cause labral tears. However, emerging literature in sports and dance medicine shows that repetitive hip end‑range loading, impingement patterns, and extreme rotation demands are associated with higher rates of labral pathology in active populations (Lewis et al., 2018; Reiman et al., 2014). The mechanism matters.

When the labrum becomes irritated, torn, or detached, the surrounding muscles often increase their activity to compensate for lost passive stability. This can present as chronic hip, low back, or pelvic discomfort that seems stubborn or recurrent.

The first line of care is often conservative: modifying movement patterns, improving hip mechanics, strengthening appropriate stabilizers, and reducing excessive torque. In some cases, surgical repair may be recommended. Even then, how you move afterward remains critical. Returning to the same movement patterns that contributed to the injury can place the joint under renewed stress.

Unfortunately, within much of the modern yoga landscape there is no universal standard requiring teachers to update alignment strategies based on current biomechanics. Western yoga certification pathways often require relatively limited training hours, which means many well‑meaning instructors are simply teaching what they were taught. This is not about blame—it is about context. It underscores why choosing an experienced teacher with specific education in biomechanics, pregnancy, and postpartum care can make a meaningful difference in protecting joint health over time.

This is why individualized, anatomy‑respectful teaching matters—especially in pregnancy and postpartum, when ligament support is already reduced and the system is more sensitive to cumulative strain.

If you are a yoga teacher reading this, I invite you to gently reflect on whether your current scope of training truly supports every student in every season—especially during pregnancy and early postpartum. Our role is not to hold onto students at all costs—an expression of Aparigraha—but to serve their long‑term wellbeing. Sometimes the most skillful and ethical choice is referral. Becoming aware of what we don’t yet know—and guiding students toward more specialized support when needed—is a living expression of Ahimsa, the practice of non‑harm. This is not a failure of teaching; it is a mark of professional integrity and care.

Training Matters

Most yoga teacher trainings do not require perinatal education.

Many instructors receive little to no formal instruction in pregnancy, postpartum care, biomechanics, pelvic floor function, or matrescence physiology. It is simply not part of the mandated curriculum and is often included only briefly under “special populations.”

And no—having given birth does not qualify someone to teach prenatal yoga any more than it qualifies a doctor to be an OB‑GYN.

It provides lived experience. It does not replace specialized training.

Pregnancy and postpartum are unique physiological transitions that benefit from informed, individualized care.

You Do Not Have to Endure This

Low back pain in pregnancy is common.

But it is not a sentence.

It is often a signal—about load transfer, stability, coordination, alignment, and support.

With the right blend of functional movement, deep core coordination, hip mobility, glute strength, and appropriate external support, many people experience meaningful relief.

Your body is not broken.

It is adapting.

And it deserves care rooted in both science and wisdom.

If you would like individualized support for low back or pelvic girdle discomfort during pregnancy or postpartum, I offer private sessions grounded in biomechanics, pelvic health principles, and trauma‑informed yoga.

Gratefully,

Anne

References & Further Learning

Liddle, S. D., & Pennick, V. (2015). Interventions for preventing and treating low‑back and pelvic pain during pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.

Mens, J. M. A., et al. (2006). The mechanical effect of a pelvic belt on sacroiliac joint laxity. Clinical Biomechanics.

Kalus, S. M., et al. (2008). Managing back pain in pregnancy using a support garment. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing.

Bowman, K. (Nutritious Movement). Squat mechanics and hamstring–pelvis relationships.

Garner, G. (Pelvic Health & Orthopedic Yoga Therapy). Hip preservation and Warrior alignment resources.

Duvall, S. (Core Exercise Solutions / PCES). Pregnancy core connection and pelvic floor coordination principles.

Richardson, C., Hodges, P., & Hides, J. (2004). Therapeutic Exercise for Lumbopelvic Stabilization. Churchill Livingstone.

Gupta, J. K., Sood, A., Hofmeyr, G. J., & Vogel, J. P. (2012). Position in the second stage of labour for women without epidural anaesthesia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.

de Jonge, A., et al. (2004). Squatting versus supine position during the second stage of labor: effects on pelvic dimensions. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research.

Bø, K., et al. (2015). Evidence‑based physical therapy for the pelvic floor. Elsevier.

Hodges, P. W., et al. (2007). Changes in pelvic floor muscle function in different postures. Neurourology and Urodynamics.

Vleeming, A., et al. (2008). European guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pelvic girdle pain. European Spine Journal.

Wu, W. H., et al. (2004). Pregnancy‑related pelvic girdle pain (PPP), I: Terminology, clinical presentation, and prevalence. European Spine Journal.

Reiman, M. P., et al. (2014). Femoroacetabular impingement and labral injury in active populations. Sports Health.

Lewis, C. L., et al. (2018). Hip mechanics and labral pathology in physically active individuals. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy.